Phase Transitions in Business Systems

Classical Analytics Fails at the Boundary

Kevin Koenitzer | February 18, 2026Classical Analytics are a risky proposition

Every business runs on heuristics. Revenue trends predict future revenue, customer retention rates signal product health, variance from budget indicates operational drift. These functional approximations allow organizations to act with confidence in the face of incomplete information, and they work…until they don't.

The problem isn't the heuristics themselves, it's that we forget they're heuristics. The model becomes the system, and even if the system shifts beneath us the model continues to tell us that we know where we are.

Classical business analytics is structurally blind to this failure mode, because its tools are built on assumptions about how systems behave that are simply wrong for the kinds of systems businesses actually are:

Linear regression assumes the relationships that held yesterday hold today, control charts assume variance is stable and forecasting models assume the future resembles the past. These assumptions are necessary simplifications, biased toward action. However, they produce a specific and dangerous blind spot: they cannot tell you when they're about to stop working.

Consider three examples where they didn't:

Blockbuster 2003. Revenue was stable, store traffic consistent, customer retention normal. The heuristic said: a company that has always made money renting physical media will continue to make money renting physical media. What the metrics couldn't see was that the underlying system, specifically customer preference and distribution economics, had already begun a phase transition. By the time the numbers moved, the transition was irreversible.

"Blockbuster Inc., the largest video rental chain, had a fourth-quarter profit of $30.7 million and forecast net income of at least $1.25 a share this year. Net income was 17 cents a share, contrasted with a net loss of $4.5 million, or 3 cents, a year earlier. Revenue rose 17% to $1.58 billion, the Dallas-based company said. Blockbuster predicted that 2003 per-share earnings would rise at least 20%. Shares of Blockbuster rose $1.35 to $14.50 on the NYSE."

— Blockbuster Q4 Earnings Report, 2003. LA Times Archives

One year later:

"Blockbuster's first earnings report since spinning off from Viacom wasn't pretty as the rental giant took a $1.5 billion writeoff and reported a net loss of $1.42 billion. The struggling company also reported a continuing slowdown in rentals and growing losses due to investments in new businesses like its online subscription service. As a result, Blockbuster shares closed at a low they haven't seen since early 2001."

— Blockbuster Session Not A Nice Sight, Variety. Published October 27, 2004.

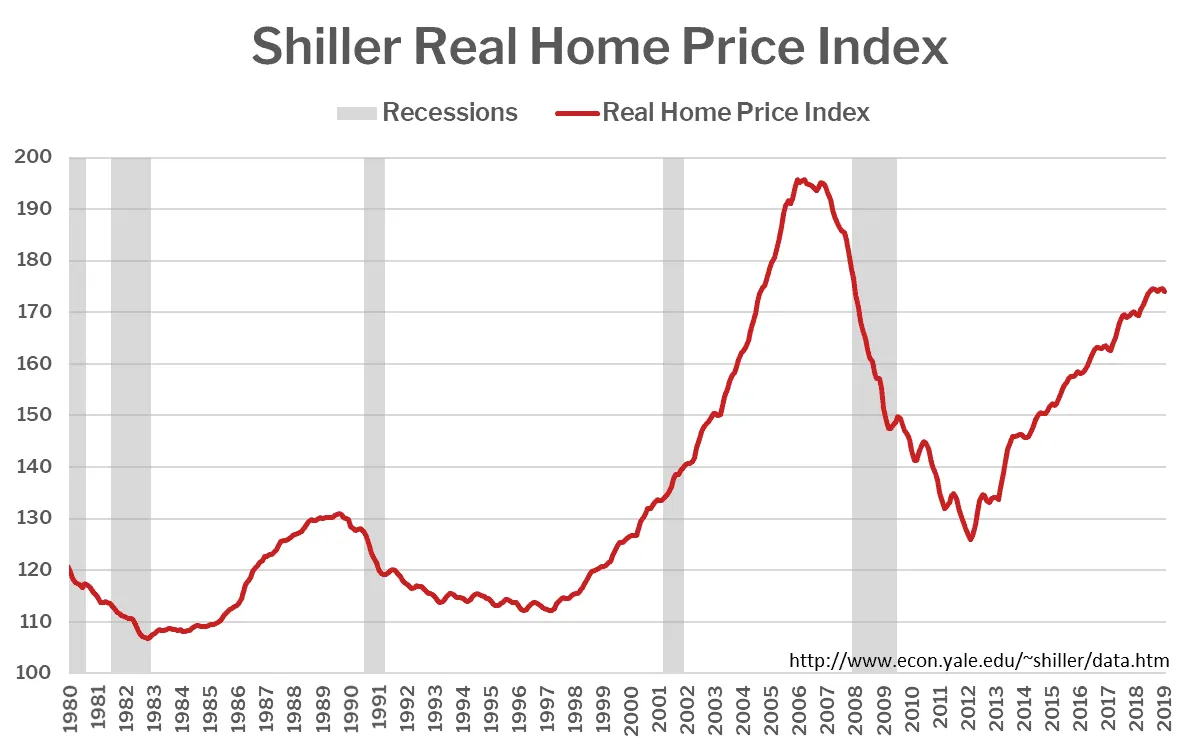

2008 mortgage market. Risk models built on historical default correlations had performed reliably for decades. The heuristic said: diversified mortgage backed securities reduce systemic risk. What the models couldn't see was that the diversification assumption depended on regional independence that evaporated under stress. The system had a hidden dependency structure that only became visible when it failed catastrophically.

The hidden dependency: Mortgage delinquencies (Source: Kathy Tran)

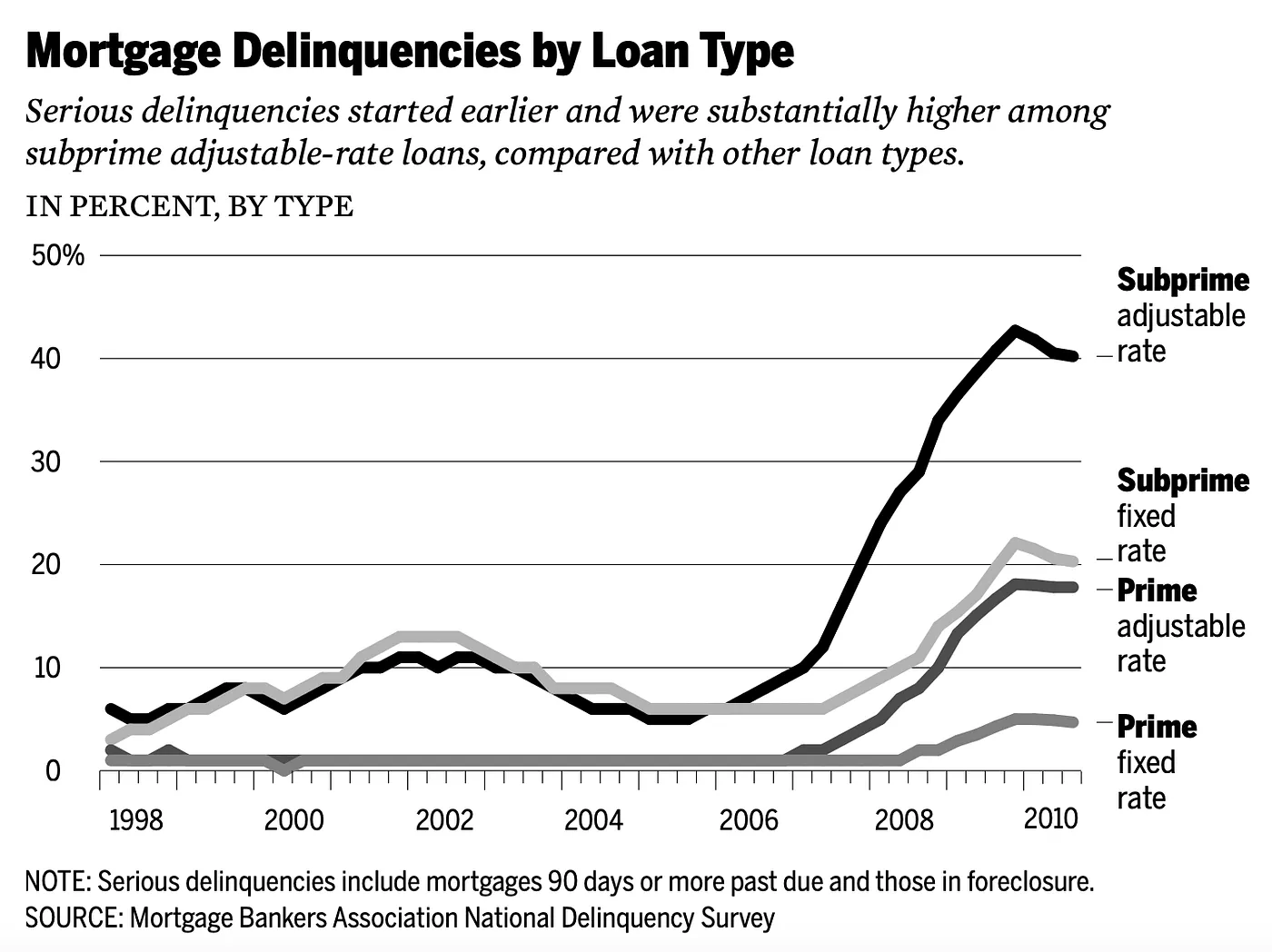

High growth SaaS, 2021 to 2022. Customer acquisition costs looked sustainable, net revenue retention strong, growth curves consistent. The heuristic said: a company growing at this rate in this market will continue to do so. What the metrics couldn't capture was that growth was being powered by a zero interest rate environment that was itself a temporary condition, not a structural feature of the market. When rates moved, the entire category repriced simultaneously.

Cumulative market capitalization of all SaaS companies (Source: Alex Clayton)

In each case the tools weren't wrong. They were accurately measuring the system they were built to measure. The problem was the system changed underneath them and nothing in the toolkit was designed to detect that change before it became visible in the numbers.

The question isn't how to build better heuristics. It's how to know when they're no longer accurate because the underlying assumptions have changed.

Failure Modes Explained

The reason classical tools fail at these moments isn't a data problem or a modeling problem. It's an issue with underlying assumptions. These tools are built on the physics of simple systems. Simple systems are linear, stable, and memoryless.

They are then applied to systems that are none of those things.

Businesses are complex systems. That word gets used loosely so it's worth being precise about what it actually means:

- A complex system has memory: what happened in the past influences how it responds to the present in ways that aren't captured by the current state alone.

- It has non-linearity: small inputs can produce large outputs, and large inputs can produce nothing, depending on where the system is in its own cycle.

- It has phase transitions: periods of apparent stability that end abruptly in a reorganization of the system's fundamental character. Not gradual change. Discontinuous change.

These properties reflect the normal behavior of complex systems: Things like markets, organizations, customer bases, and competitive landscapes, and classical tools don't capture these properties at all.

Statistical Mechanics and Complexity Theory

Complexity science offers a different lens: Rather than asking what the system's current state predicts about its future state, it asks what the system's behavioral signature reveals about its underlying character.

- Is it trending or mean reverting?

- Does it have long range memory or is each observation essentially independent?

- Is its internal structure becoming more rigid or more flexible?

- Are there signs that it's approaching a transition before that transition shows up in the numbers?

- Are any of these behaviors changing over time?

The specific signals complexity science looks for are subtle but measurable:

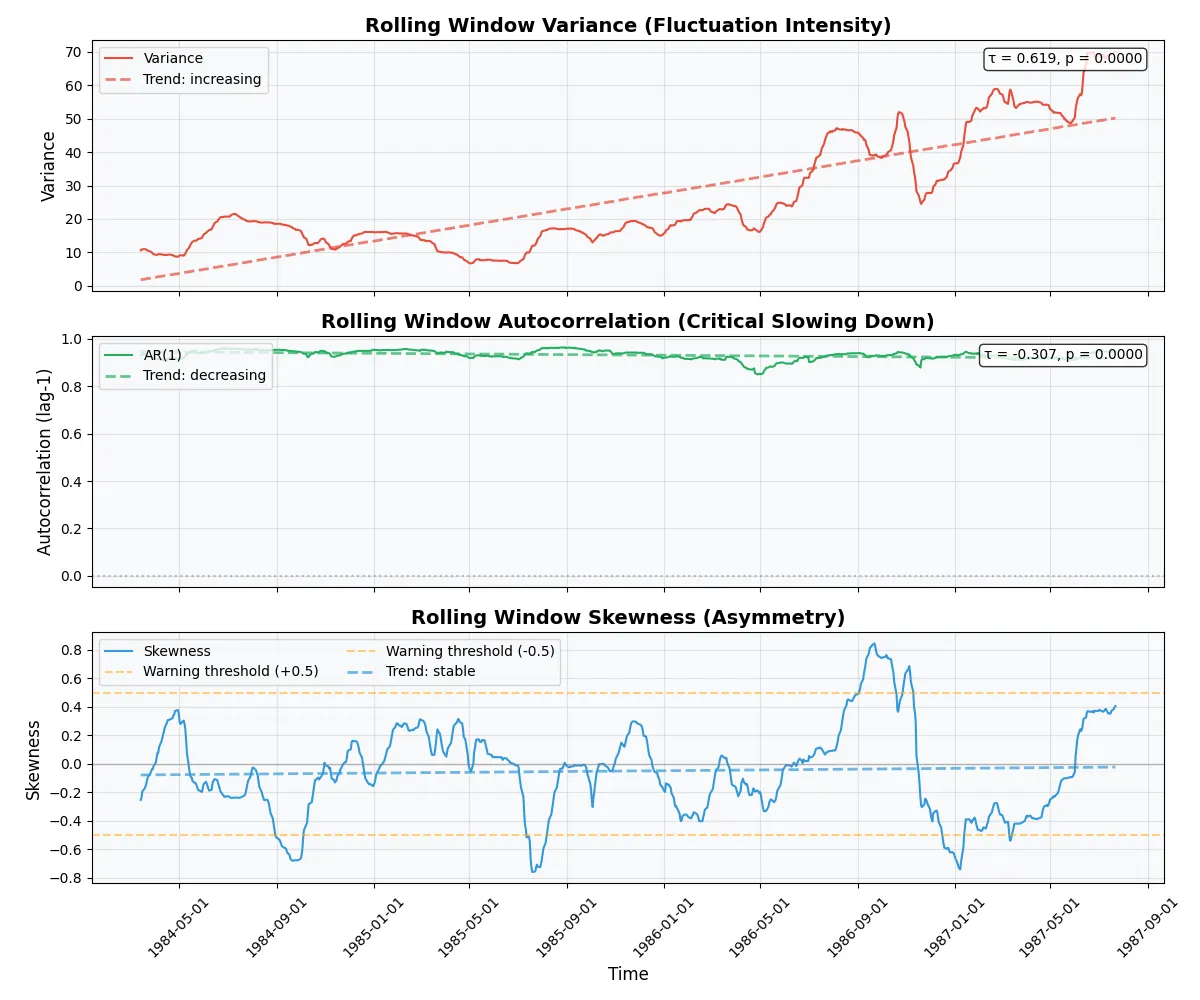

- Variance that begins rising before a transition.

- Autocorrelation that increases as a system loses its ability to recover from perturbations.

- Entropy that shifts as the system's internal pattern structure changes.

- Fractal memory embedded in the time series that reveals whether momentum is structural or illusory.

- Log periodic oscillations that accompany the kind of accelerating growth that precedes collapse.

None of these replace the heuristics, but they can tell us when a system is changing underneath our feet which is exactly when our existing heuristics are most likely to fail.

Case Study: Didier Sornette's work on the 1987 Stock Market Crash

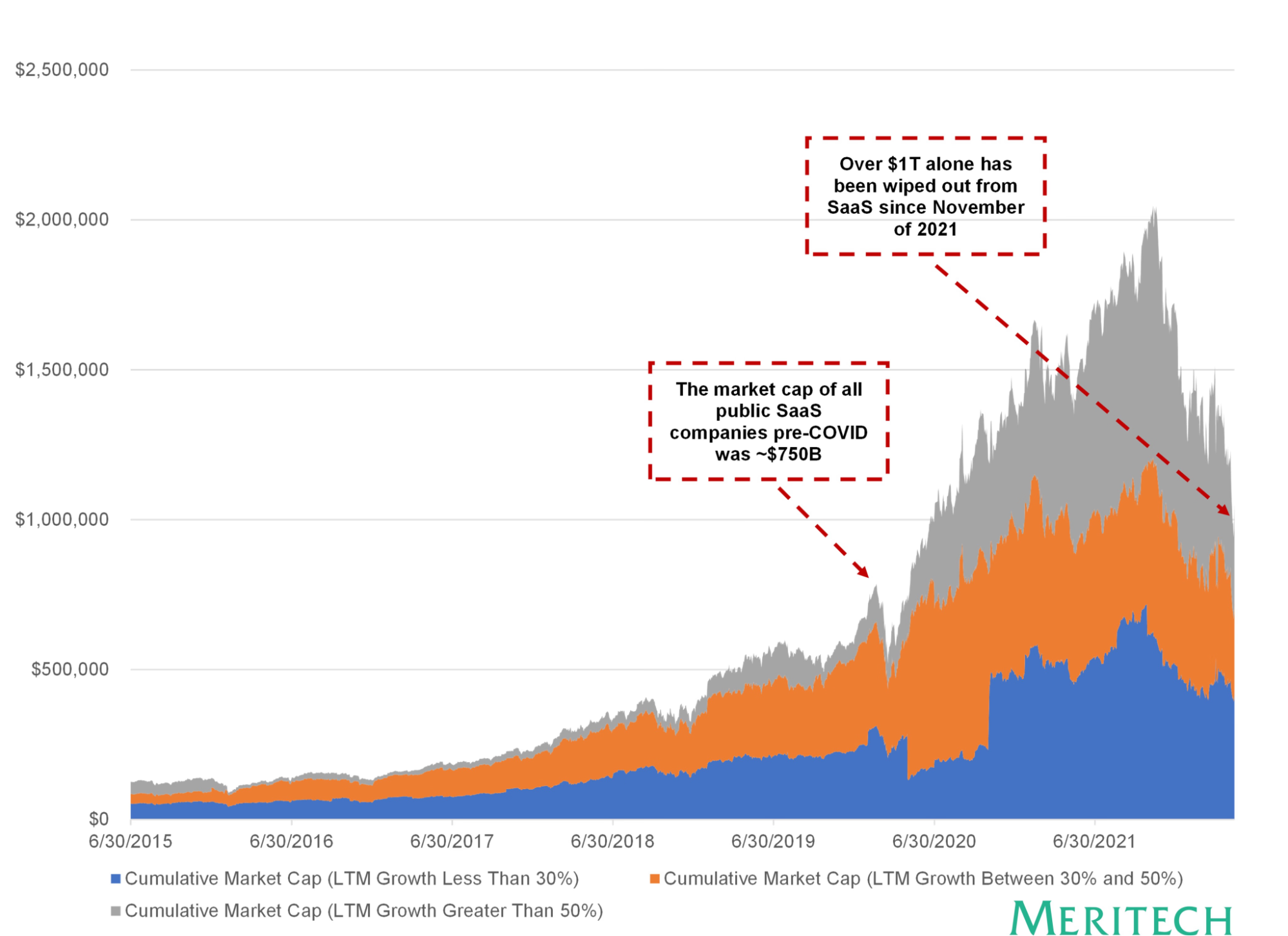

In 1987 the S&P 500 rose steadily for years, then lost 22% of its value in a single day. By every classical measure available at the time, the market was healthy. Volatility was moderate and the market trend was positive. Nothing in the standard toolkit indicated that October 19th would be different from October 18th until it was over.

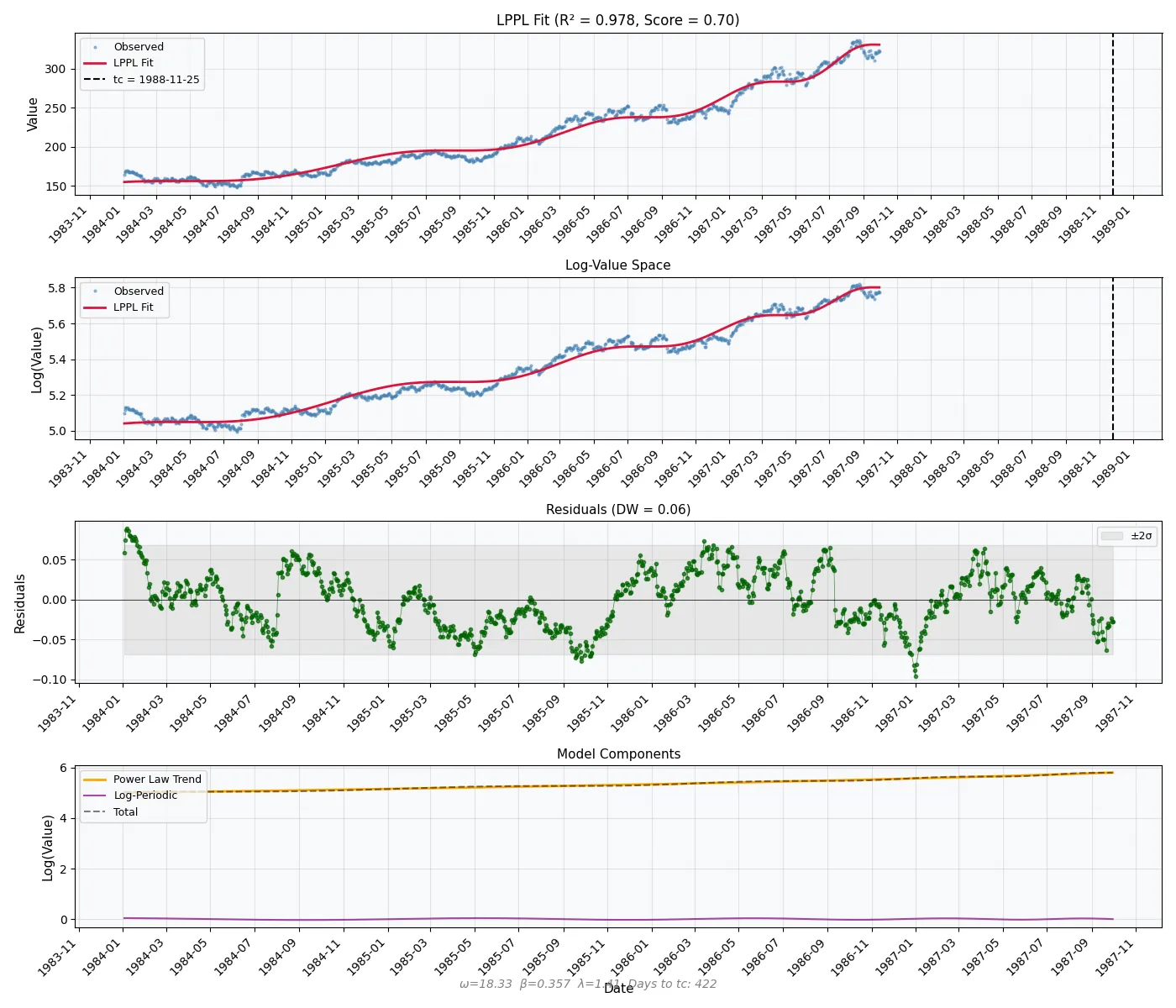

Didier Sornette, a physicist studying material failures, noticed retroactively that in the months before the crash, the market had been exhibiting a specific pattern: Accelerating growth punctuated by oscillations that were themselves accelerating, following a precise mathematical signature he recognized from the behavior of materials approaching a breaking point. The stock market was exhibiting the behavioral fingerprint of a system approaching criticality. He published his research on LPPL models applied to stock market data in a 2003 paper titled "Critical Market Crashes".

Our contribution – Complexity measurement pipeline

At Snowpack, we often run into situations where clients struggle with the consequences of a decision they've made under the wrong assumptions. It's not that they are ignorant, but rather that they are making decisions based on straightforward assumptions about a complex system that is, in reality, rapidly changing beneath their feet.

There has been a lot of research since the turn of the 20th century on managing randomness and uncertainty, particularly in physics and later in the finance industry, but it hasn't really made its way into the realm of modern business.

We asked ourselves whether the existing tools in the fields of statistical mechanics and complexity theory could be used in cooperation with one another to give us a measure of instability in business; to tell us when the landscape is shifting.

We developed a five-stage analytical pipeline (Entropy → Hurst → EWS → RQA → LPPL), that progressively characterizes system complexity, memory structure, transition proximity, dynamical regime, and singularity risk. Each stage of analysis is grounded in seminal publications from academic literature in physics and mathematics and validated against both financial market data and real-world business operational data.

Snowpack Data's Complexity Analysis Pipeline Phases

| Stage | Method | Diagnostic Question |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Entropy Analysis | How complex/predictable is this system? |

| 2 | Hurst Exponent | Does this system have memory? What kind? |

| 3 | Early Warning Signals | Is the system approaching a critical transition? |

| 4 | Recurrence Quantification | What is the dynamical regime? Has it changed? |

| 5 | LPPL Detection | Is this system in a super-exponential bubble/collapse trajectory? |

Testing the model

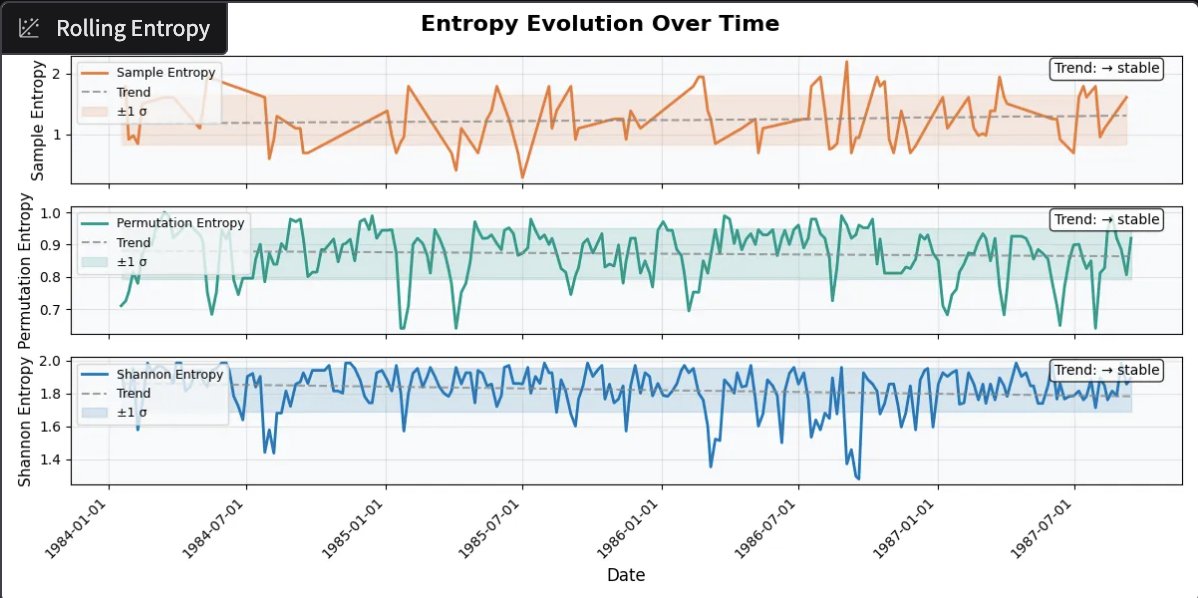

We ran daily S&P data spanning from the start of 1984 all the way up to the day before the crash (October 18, 1987) through a unified complexity diagnostic pipeline that combines five independent measures — entropy, fractal memory, early warning signals, recurrence structure, and Sornette's own log periodic power law model. The results were unambiguous:

Entropy was low and structured, indicating the market was following a highly constrained trajectory with 80% predictability.

Entropy measures from 3 separate methods (Shannon entropy, permutation entropy, and sample entropy) all showed stable trending in the data.

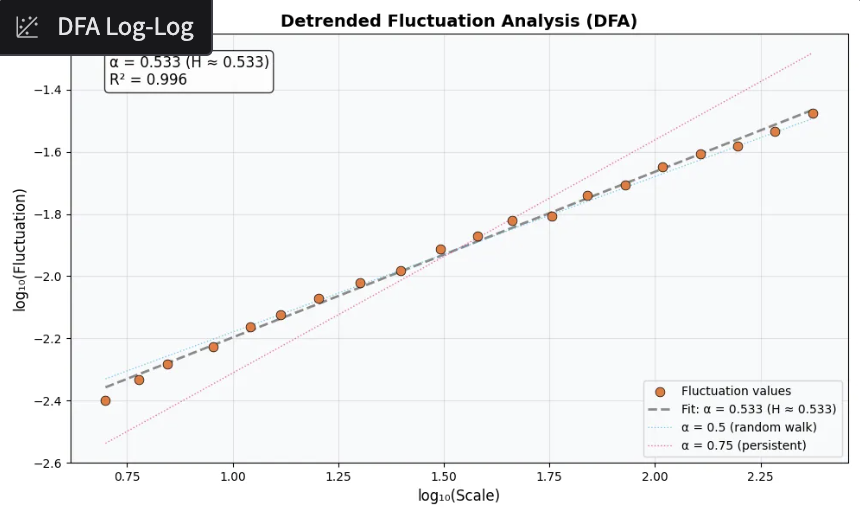

The Hurst exponent confirmed weak but real persistence.

H = 0.53 indicates weak persistence. There is mild trending behavior where movements in one direction have a slight tendency to continue. This suggests some directional patterns may exist.

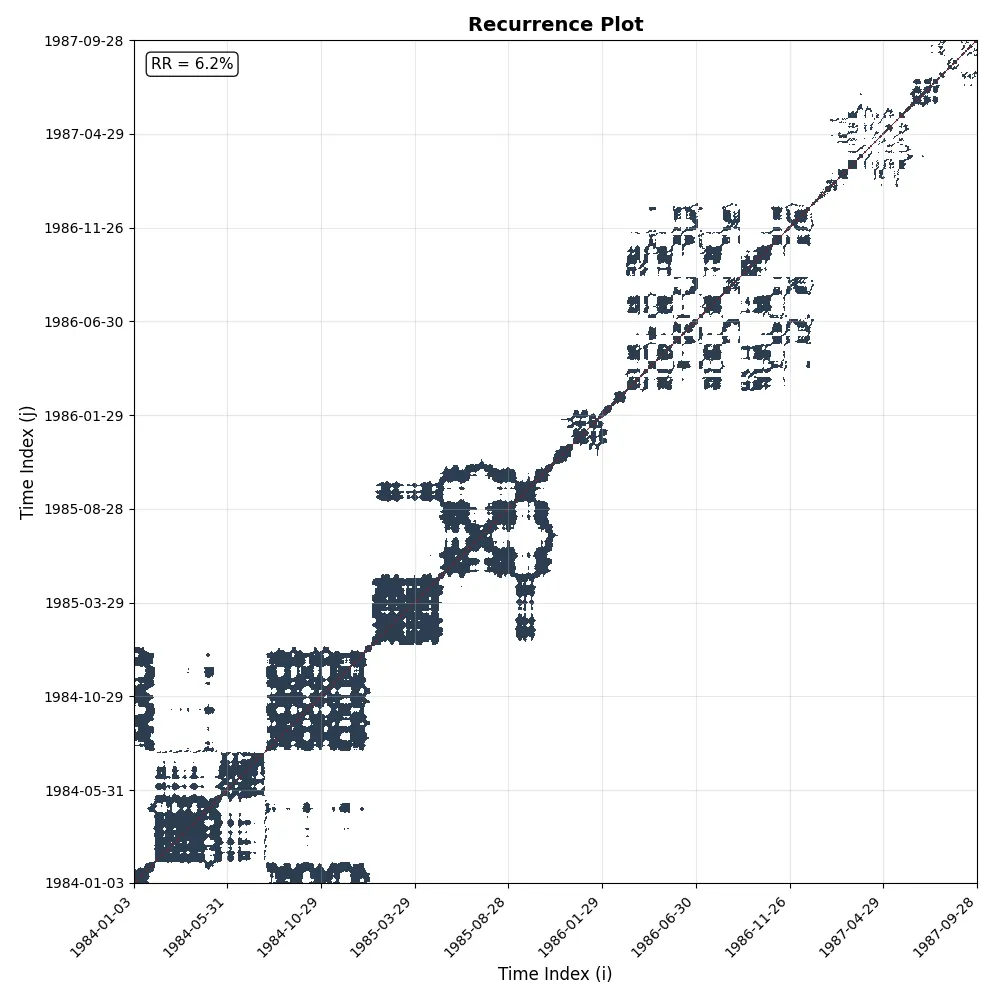

Recurrence analysis showed 98% determinism and 99% laminarity: the system was locked into a path, repeating its own geometry with almost no flexibility.

Overall Pattern: Mixed Structure. Detail: Both diagonal and vertical structures present (complex dynamics).

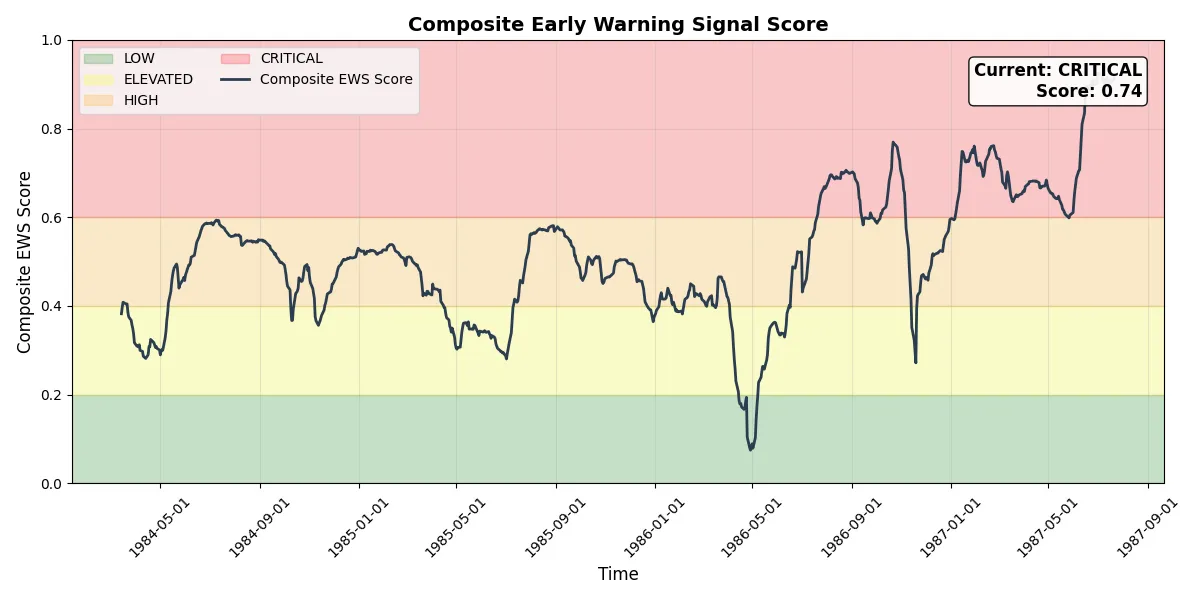

Early warning signals were elevated, with variance and kurtosis both active.

The LPPL model detected the log periodic signature with high confidence, pointing to a critical transition window around November 1988 (a year late, but still within a reasonable 12-month range).

Moderate acceleration pattern detected. The system shows clear super-exponential growth with balanced intensification. Low DW score suggests high complexity and randomness not accounted for in the LPPL model.

| InterventionMethod | Applicability | Confidence | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perturbation | Not Effective | 90% | System is in a rigid, brittle state (DET=98.0%, LAM=98.6%) near criticality. Perturbation is unsuitable because small interventions can trigger cascading regime transitions with unpredictable magnitude and direction — not because of the statistical memory (H) of the series. The system has lost flexibility; it is locked into a trajectory. |

| Structural Change | Not Effective | 90% | System may be transitioning on its own. Structural intervention is unlikely to prevent transition if criticality indicators are genuine. Focus resources on monitoring and preparation for the post-transition regime. |

| Active Monitoring | Recommended (Freq. Daily) | 90% | URGENT: System exhibits characteristics associated with imminent regime transition. DET=98.0%, LAM=98.6%. LPPL suggests potential transition window around 1988-11-25. Monitor continuously. Implement protective measures. System predictability horizon is 8-15 steps (moderate). |

The table above shows an assessment of possible intervention methods to manage the system characterized by the data. This was generated by our pipeline model, and characterizes the S&P 500 Index as being in a state of accelerating change and brittleness.

The Uncanny Valley Effect

The system classification from our pipeline was unambiguous: rigid, pre transition, high confidence, high transition risk. From a classical measurement perspective, standing on the edge of a massive precipice looks exactly like riding a rocketship to the moon.

The deep sea anglerfish from the Spongebob Movie captures the point perfectly, we think.

By contrast, standing at the precipice of a positive inflection point feels much the same as living in a stable regime. The point is, if you're using classical measurement techniques, the ground starts shifting before you actually notice it; and by the time you do, it's probably too late.

Tim Urban's AI article from a decade ago captures the inverse well, too.

Our Results

Unlike Sornette's 2003 paper, the point isn't that the pipeline predicted the crash. In fact, for the purposes of this analysis we don't even really care about that: The point is that it characterized the system honestly.

Though the results were not screaming "bubble" as Sornette's did, what we saw from the data was a system that was changing more and more rapidly over time.

In fact, these results are less absolute and more ambiguous than Sornette's but that is not a bug, it's a factor of the real complexity inherent in the stock market, and supports the fact that single modes of measurement, parameterized in different ways will lead to different outputs.

By running these models in unison across a range of parameter values, we can get a clearer picture of whether the data is showing consistent signs of behavioral change, or whether it is so full of randomness and noise that it's not possible to get a good idea of the underlying properties of the system. Every result gives us an idea of whether our pre-conceived notions of what the system is and the way it behaves are likely to be accurate (now, and over time).

Nobody Likes Being Wrong

The purpose of implementing complexity measurements to understand your business is not to predict future behavior. It is to understand with greater clarity:

- What you are even looking at.

- Where the limits of your knowledge are.

- Whether your baseline assumptions are likely to be accurate.

Even in cases where the models "fail", it provides us with useful information; namely that the data is too complex or too erratic to exhibit predictable behavior, and this pushes us to adjust our mental models and expectations accordingly.

In the example above, our pipeline structure identified the behavioral signature of a system that had lost flexibility, was locked into an accelerating trajectory, and was approaching a discontinuity. Where classical tools saw a healthy trend, the complexity diagnostic saw brittleness.

This is the difference between classical metrics and complexity metrics: Not better prediction, but rather better characterization of when our existing prediction models are about to break, and this constitutes a complementary dimension of analysis that is absolutely key to measuring system health, that business practitioners overlook today.

Practical applications

If as an executive you're weighing whether to take a big swing on a marketing campaign, acquisition, or another type of investment that would constitute a structural change to your business–it makes sense to first determine whether that swing is likely to lead to the outcome you're looking for.

If your sales and marketing clicks show strong trending behavior–those marketing campaigns will help grow the business, but if your sales and clicks are mean-reverting, it'll be like throwing a stone into a river: The campaigns will only show up as a blip on the radar before the ripples it causes disappear are absorbed back into the stable, constant flow of the river downstream.

If as an investor, the company you're thinking of acquiring is showing stable, persistent growth over time–you might expect its valuation to more accurately reflect its intrinsic value than if it's showing viral, bubble-like growth characteristics. You might draw different conclusions about whether you're getting a good deal or if you're overpaying for something that is growing at an unsustainable rate. If you're in PE you might choose to self-select for acquisition targets that exhibit stable systemic behavior. A VC might elect to invest in companies likely to exhibit a propensity towards virality. A retail investor preparing for retirement might want to avoid equities exhibiting bubble dynamics at all costs.

In all of these cases, understanding system complexity is a key part of making the best possible decision across a range of decisions with different possible outcomes.

As a manager, investor, trader, or executive, the behavior of the system you operate in, and your knowledge of its complexity directly impacts your ability to assess the validity of the mental models you use to inform the decisions you make. If you don't know how it behaves you're just relying on the system not changing, and when it inevitably does your luck will run out.

Parting thoughts – The limits of complexity measurement, Feynman, and AI

This topic came about specifically because we've been working on quite a few AI implementation projects lately, and we're constantly being asked to explain how and why these complex models do what they do, as well as measure their impact on already complex business processes and systems, made only more complicated by the addition of artificial intelligence and automated decision-making processes.

One of the toughest challenges we face today in business is accurately assessing the impact, positive and negative, that these new technologies are having on the way our systems function. One thing we do know for sure is that their addition has led to changes in behavior in systems that have been stable for decades, and that we don't have a good way of understanding how fast that change is occurring, or how far-reaching it is likely to be.

While complexity measurement doesn't give us all the answers, it at least allows us to characterize the behavior of the systems around us in a manner that tells us when we might be hanging on to mental models and assumptions that no longer hold, and that's a very valuable proposition in our current climate.

Philosophical waxing

"If you think you understand quantum mechanics, you don't understand quantum mechanics."

— Richard Feynman, American Theoretical Physicist

Statistical mechanics and complexity theory are both related to quantum mechanics, and the famous Feynman quote holds true for these disciplines as well: Managing complexity is…complex. The deeper you go into the subject, the more you realize how impossible it is to be sure of what you know about the world around you and the way it really works.

The hard limitation here is that this framework won't tell you what to do.

It tells you when to stop trusting the tools that are telling you what to do. In a world where the most dangerous moments, or budding opportunities, are precisely the ones where your dashboard looks the most confident or most stable, that's not a small insight. The decision you then make is up to you as an executive, investor, operator; as a person.

This is a high-level blog article covering the work we're doing around bringing complexity theory and statistical mechanics into the realm of business management. We'll be publishing an extensive white paper on the subject, with examples, methodologies, and a full breakdown of the pipeline in the coming months.