Federated Datasets

A guide to building useful (and useable) datasets.

David Olodort | January 28, 2025Introduction

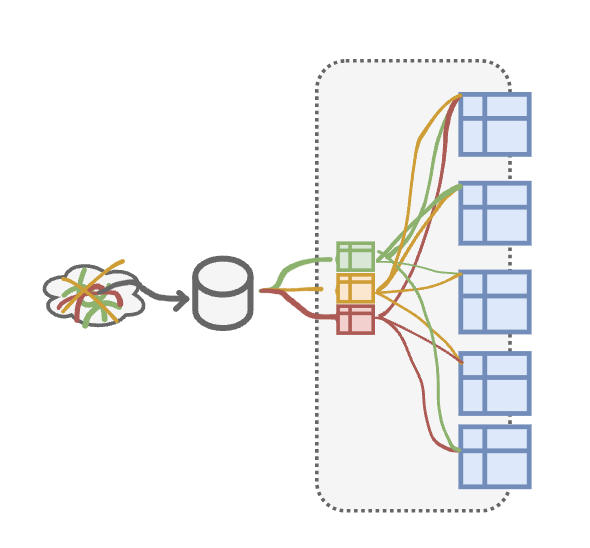

Traditional data stacks often follow a piecemeal approach to their development lifecycle:

- Raw data is piped into the data warehouse where it is cleaned.

- That data is combined with other data into consumer models that contain data categorized based on business logic.

Whenever the business finds that the consumer model’s semantic definitions need updating, a request is made to either:

Whenever the business finds that the consumer model’s semantic definitions need updating, a request is made to either:

- Change an existing model’s logic to reflect that business user’s needs.

- Build a new model that defines the data slightly differently.

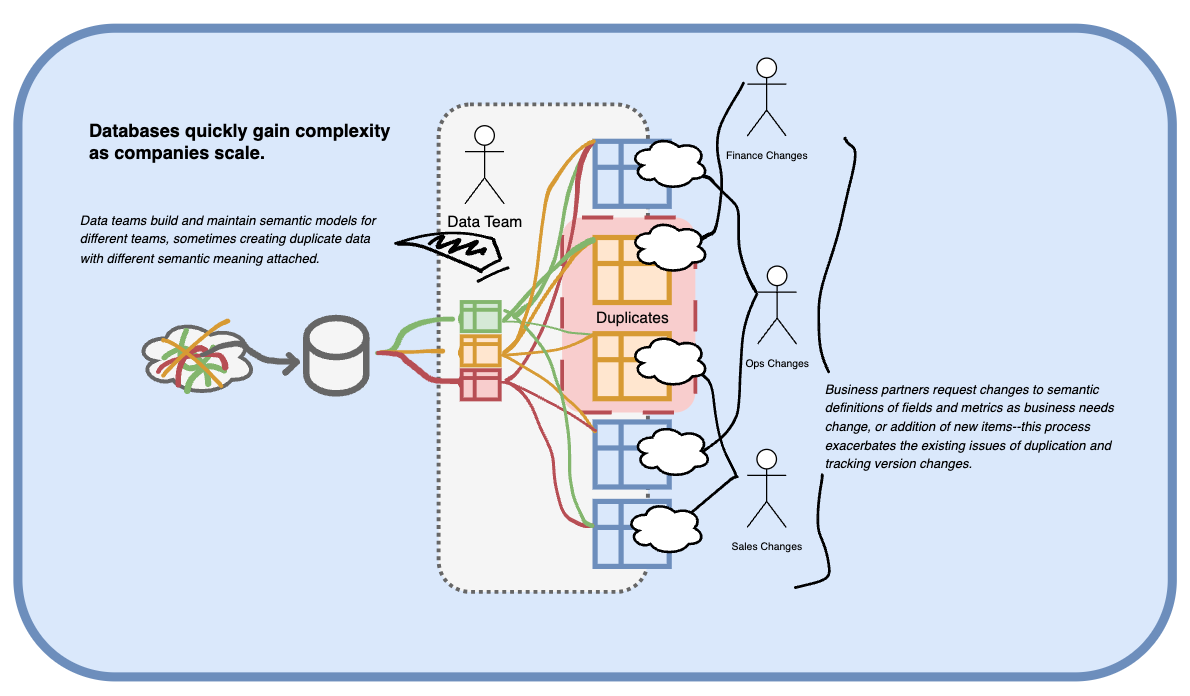

In the beginning this model is not problematic, but the risks associated with a standard development model present themselves as businesses scale:

- Volume of data transformation and re-definition requests increases in line with staffing increases and company growth.

- Business processes and products become more complex, necessitating more complex data structures and definitions.

- Competing priorities across business units lead to the development of multiple data models sharing similarities, but with slight differences.

- These models are used to generate metrics that are variations of the same number, filtered differently or stemming from different source models that create multiple sources of truth.

The consequences of these issues constitute a breakdown of trust in the data, and a slowdown in the decision-making capabilities of the organization. They also lead to the proliferation of duplicative data properties whose costs can quickly spiral out of control if they are not carefully managed.

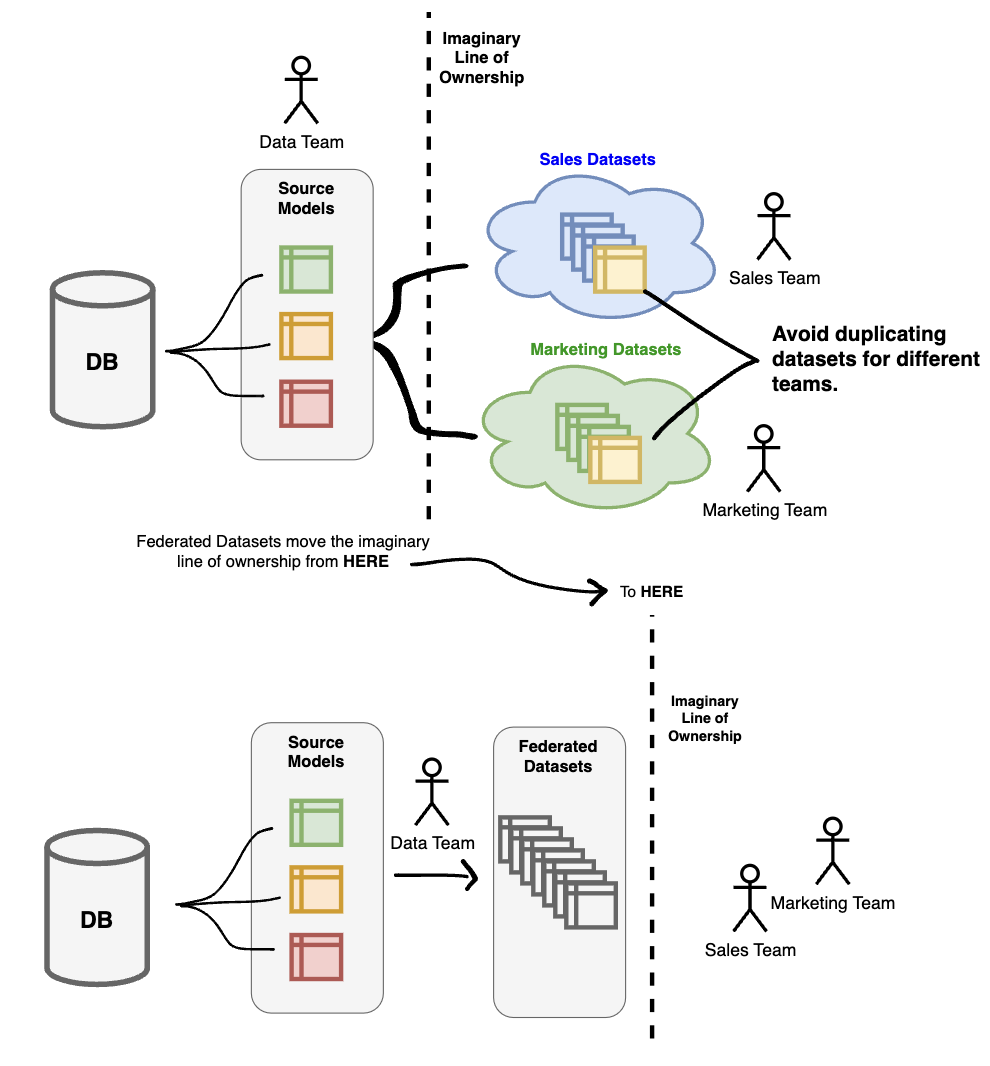

The federated data product approach

The solution to data challenges that occur as a function of rapid scale and added complexity over time focuses on empowering the data organization to be the arbiters of what is–and what is not–considered “accurate” data. It also places responsibility on the data team to produce a set of rigorously managed data resources (i.e. consumer models, analyses, metrics).

We call these data assets federated–meaning they are centrally owned by the data team, but each business unit maintains some autonomy over the data by being allowed to add/change the semantic meanings associated with the data their business unit uses–with oversight from the data team.

Federated datasets follow two specific rules that ensure they stand above all other forms of data in the organization:

1. The federated models, their sources, and their downstream product outputs are traced back all the way upstream and confirmed for accuracy on a consistent basis.

- This requires setting up a series of tests that run as new data are loaded and establishing metrics that ensure updates from source systems are consistent over time.

- Defining these tests involves conducting analysis on each data source with the goal of establishing an expected baseline of values/thresholds.

- The tests measure new data being brought into the warehouse against the expected values/thresholds and raise a flag to the engineers when an unexpected result is produced.

2. The definition of each column of data in a federated model is carefully and transparently recorded.

- This requires a data dictionary containing the definitions of each column and specifying the way the values in that column are collected, derived, or calculated.

- This is actively managed by the data team in cooperation with the business units. As definitions change the data team ensures accuracy and quality within the federated datasets.

- End-users can access the data dictionary to understand the data they’re using when they self-serve for ad-hoc analysis, or to build new metrics or dashboards.

Step one ensures that no part of the data ingestion or transformation process is hiding or misrepresenting the data in any way:

When we present an analysis to a stakeholder, or an end-user accesses our federated models to build their metrics using this model, we have the confidence to assert that any insights or metrics derived from these sources are built upon a base that has been rigorously and consistently tested and validated for accuracy.

Step two ensures that people have a clear path to understanding exactly what the data they’re looking at (or using for metrics/analysis) actually are:

When we ask how metrics are calculated, or how certain data is derived we rely on a robust data dictionary to either confirm the metric in question is accurate, or highlight a mistake in definition or logic that may have skewed our results.

Why do this at all?

These two steps, and the associated workflows and processes give us a shared understanding of what is considered “correct” or “accurate” from both a source standpoint, and a definitional standpoint.

This gives the analyst or business user generating the report confidence that the data they’re using is fully defined and therefore interpretable, and it gives the stakeholder a point of reference from which to assess competing sources of data or truth that are brought in front of them.

A note on competing sources of truth: The purpose of setting up federated datasets is not to ensure that people only use these data and their associated definitions for analysis–It sets an organizational standard for the level of rigor required to state confidently that insights derived from data or metrics are correct.

Putting it into practice

Users within the organization are welcome to source and model their own data to achieve their desired results, with the caveat that if those users produce a metric or data output that is similar to a federated one, and can’t produce evidence of having used a similar level of rigor in terms of ensuring accuracy of data and definitions when deriving those outputs–the validity of their data is called into question and can be thrown out in favor of the federated metric.

In this way, you pivot from a data infrastructure that allows people to create multiple, competing sources of truth, to a system with one source of truth (federated datasets, metrics, reports), that can only be undermined by a new source of truth that has been vetted as rigorously as the existing one.

People are still free to create their own metrics and dashboards, but under this system executives are also empowered to throw out those individuals’ results out if they conflict with the established sources of truth unless those individuals can prove their new source of truth correct by undergoing the same data source vetting and data definition process when deriving their new metrics and dashboards.